Why "AI patent search" is not what you think it is — and why it matters

The conversation around AI and patent practice has arrived. But the clarity hasn't.

In the past two years, IP professionals at every level have begun experimenting with AI tools to accelerate their work. Some of those experiments have been productive. Many have been frustrating. And a significant number have produced outputs that looked compelling until someone with real patent expertise examined them closely.

The problem isn't that AI doesn't belong in patent practice. It does, and it's here to stay. The problem is that the tools being reached for most often — public large language models, basic search integrations, and free-tier AI assistants — are not built for this work. And two specific misconceptions are driving practitioners toward tools that can't deliver what they need.

Understanding those misconceptions is the first step toward building a workflow that actually holds up.

Misconception one: Public LLMs can evaluate patents.

It's a natural instinct. If a large language model can summarize a contract, draft an email, or explain a complex technical concept, why can't it evaluate a patent? Some people who likely know better use this misconception to judge all AI as a means to resist change and adoption.

The answer lies in what these models actually are and what they actually know.

Public LLMs — ChatGPT, Gemini, Perplexity, and their equivalents — are trained on broad corpora of text. They are remarkably capable at tasks that involve language generation and summarization. What they are not is a patent intelligence system. They do not have structured, indexed access to the patent corpus. They cannot reliably retrieve specific claims, compare claim language against cited references, or ground their analysis in actual documents. When they appear to do these things, they are often generating plausible-sounding output from training data memory — not performing genuine analysis. For a professional producing work product, that distinction is not a minor caveat. It is the entire ballgame.

The practitioners who have pushed hardest on free LLMs for patent evaluation have largely reached the same conclusion: the outputs are fluent, the citations are unreliable, and the analytical reasoning doesn't survive scrutiny. Patent prosecution and drafting require precision that general-purpose AI tools are not architected to provide.

Misconception two: "Semantic Search" means asking an LLM a question.

This one is subtler and, in some ways, more consequential — because it affects how practitioners evaluate the tools that are actually designed for patent work.

Semantic search has become a widely used term in the IP technology market, and it means something specific. It does not mean typing a natural language question into a chat interface and receiving an answer. That is an LLM. Semantic search is a distinct and technically demanding infrastructure: purpose-built embedding models that encode the meaning of patent text at a granular level, indexed vector databases containing structured patent data, reranking layers that evaluate relevance with precision, and guardrails that keep results grounded in actual documents.

When built well — as FluidityIQ has built it — semantic search understands the conceptual meaning of an invention, not just its keywords. It surfaces conceptually similar prior art that Boolean queries would never find, because it is reasoning about meaning rather than matching strings. It is, by a meaningful margin, the most powerful retrieval methodology available for patent search.

But it is infrastructure, not a chat window. And conflating the two leads practitioners to either underestimate what true semantic search can do, or to overestimate what a general-purpose LLM can deliver when pointed at a patent question.

The right architecture: FluidityIQ's MCP tools combined with an enterprise LLM.

Understanding what semantic search actually is makes the value of the right architecture much clearer.

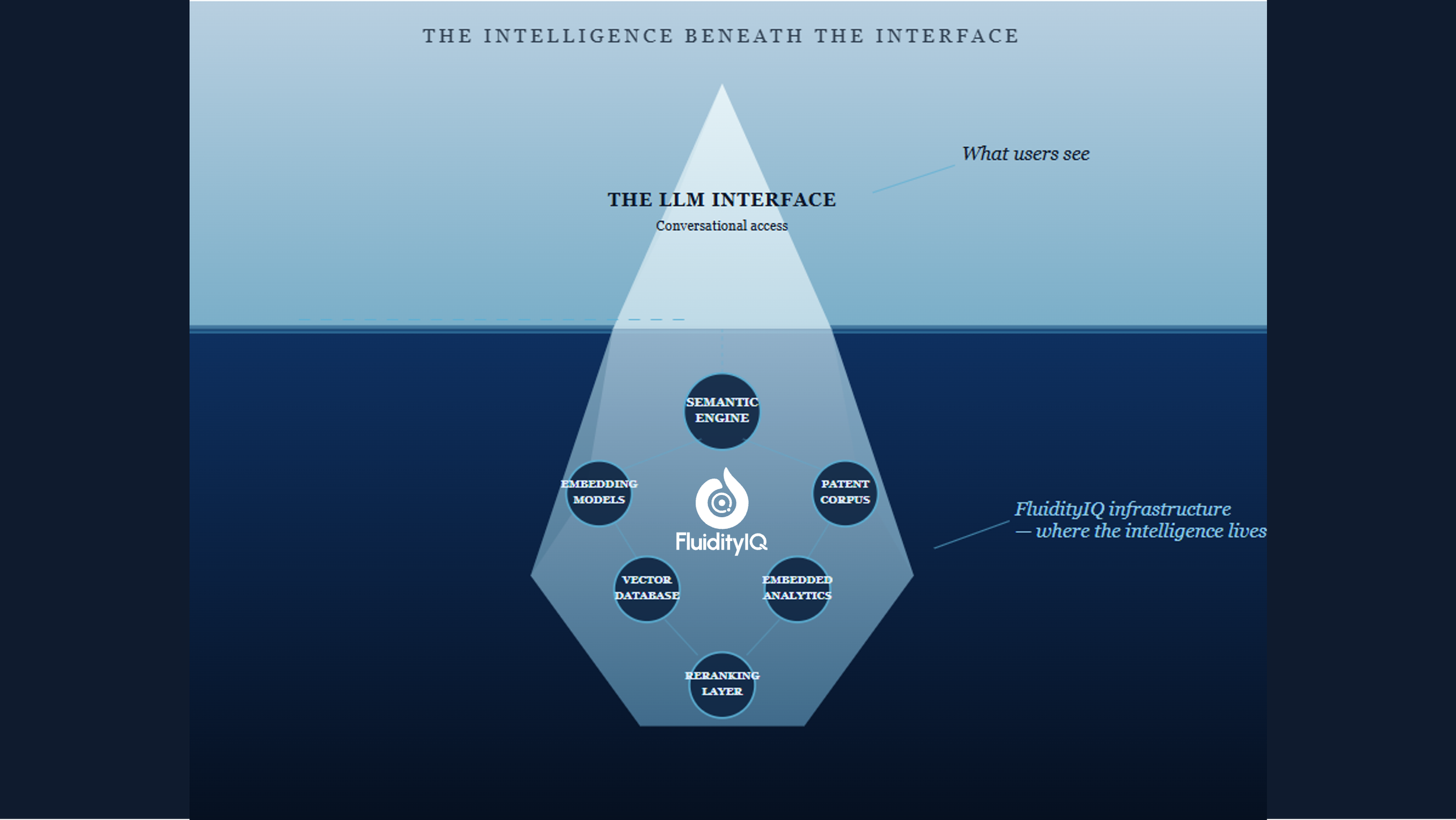

FluidityIQ's Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools connect a practitioner's enterprise LLM — Claude, for example — directly to FluidityIQ's semantic search engine, embedded analytics, and structured patent database. The LLM is not doing the analytical work. It is the conversational interface that makes the complexity of that infrastructure seamlessly accessible to a human operator.

This is a meaningful distinction. The intelligence lives in FluidityIQ's ecosystem — the semantic engine, the embeddings, the indexed patent data, the analytics. What the LLM provides is accessibility: a natural language interface through which a practitioner can interact with that ecosystem without needing to understand or manually navigate its underlying complexity. The result is a workflow that feels conversational but is grounded in purpose-built patent infrastructure at every step.

That architecture is what makes the outputs professional-grade. Every result is anchored to actual documents, specific claims, and retrievable references — because the retrieval and analysis is being done by systems built for exactly that purpose. The practitioner can iterate, drill into specific claims, compare references across a landscape, and synthesize findings without switching platforms or manually moving data between tools. The LLM makes that possible. FluidityIQ's infrastructure makes it defensible.

Where this architecture changes patent practices.

Drafting: Moving the critical iteration earlier.

AI-native drafting tools have made genuine progress in generating application language and structuring claims at speed. But drafting tools are fundamentally writing assistants. They generate language. They cannot tell you whether that language is defensible against the prior art landscape surrounding it.

Claims drafted without that intelligence are drafted in relative isolation. The question of whether they will survive examination is left to be answered later — by an examiner, at the cost of time, money, and scope.

FluidityIQ's intelligence changes this by evaluating proposed claim language against the live prior art landscape before an application is filed. The critical iteration — the one that actually determines claim scope — happens at the earliest and least expensive moment in the process, when a practitioner still has full freedom to adjust. The best time to test a patent claim is while you still have the freedom to change it.

Prosecution: Turning office actions into opportunities.

When an examiner issues an office action citing prior art against pending claims, the analytical work that follows is among the most consequential in patent practice — and among the most time-intensive. A practitioner must understand how the cited references actually read against specific claim language, identify inconsistencies or overreach in the examiner's reasoning, and develop an amendment strategy that preserves scope while overcoming the rejection.

A old school search platform can retrieve the cited references. It cannot do any of the rest of that work.

FluidityIQ's MCP-enabled workflow brings patent intelligence directly into the prosecution response process. An enterprise LLM, operating over FluidityIQ's structured patent data, can analyze examiner-cited references against pending claims, surface gaps in the examiner's reasoning, and help a practitioner develop amendment and argument strategies grounded in the actual prior art record. The practitioner retains full judgment and oversight. The intelligence arrives when it is needed, in the environment where the work is already happening — not as a separate research task requiring manual synthesis afterward.

Intelligence across the IP lifecycle.

The market for AI patent tools is consolidating rapidly around two poles — search and analytics on one side, drafting copilots on the other. Both are beginning to move toward each other, and the direction of travel is clear.

But not all integrations are equal. A prior art widget that returns a list of documents is retrieval dressed up as intelligence. It surfaces references and leaves the practitioner to manually interpret what those results mean — whether they are mid-draft or responding to an examiner.

What FluidityIQ brings — through its semantic engine, embedded analytics, deep research capability, and MCP connectivity — is categorically different. The difference is not whether a tool has access to prior art. It is whether the intelligence behind that access can answer the questions that actually matter, at each stage where patent rights are determined.

The professionals and organizations who build their workflows on that foundation — combining FluidityIQ's purpose-built patent intelligence with the reasoning power of an enterprise LLM — will file stronger patents, spend less in prosecution, and build more defensible portfolios.

The tools exist. The architecture is clear. The question is whether your workflow is built on retrieval or on intelligence.

Discover how FluidityIQ can help your organization develop its own innovation ecosystem based on your in-house expertise, not a vanilla platform. Reach out to us at info@fluidityiq.com or schedule a demo today!